Differences between Sacchi’s, Klopp’s and Guardiola’s Counterpressing Concepts

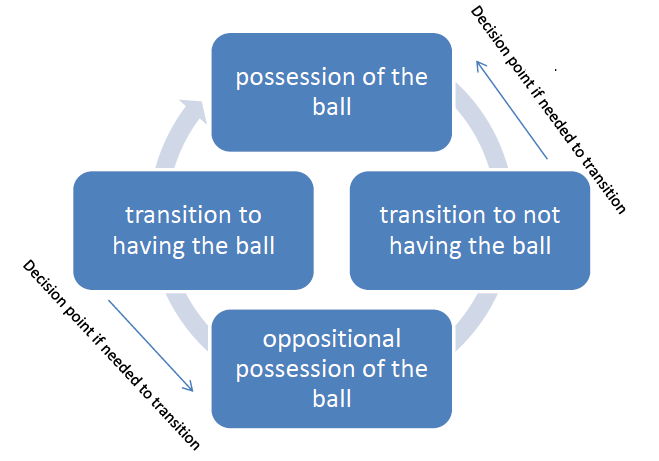

Counter- or Gegenpressing is, in its core, a very simple and understandable concept. It just means that the team immediately after losing the ball tries to press against the ball to prevent an oppositional counter and – instead of transition into the ordinary defensive organization, whatever it may be – being able to immediately get into possession again.

For exact details on counterpressing, you can read up on it in this article the basic aspects of it, here you can find variations and in this German article I have tried to cover everything I could think of within 7500 words.

In the history of football “Counterpressing” is not a really new concept. The big Dutch teams – Ernst Happel’s Feyenoord, Rinus Michels’ Ajax Amsterdam and the Dutch National team with Johan Cruijff as captain – already used it; other teams before them also intuitively pressed immediately when losing the ball.

The Busby Babes for instance were never lauded as a great tactical side, but they already displayed short passing football with mostly zonal marking and immediate pressing when losing the ball to prevent the opponent from countering.

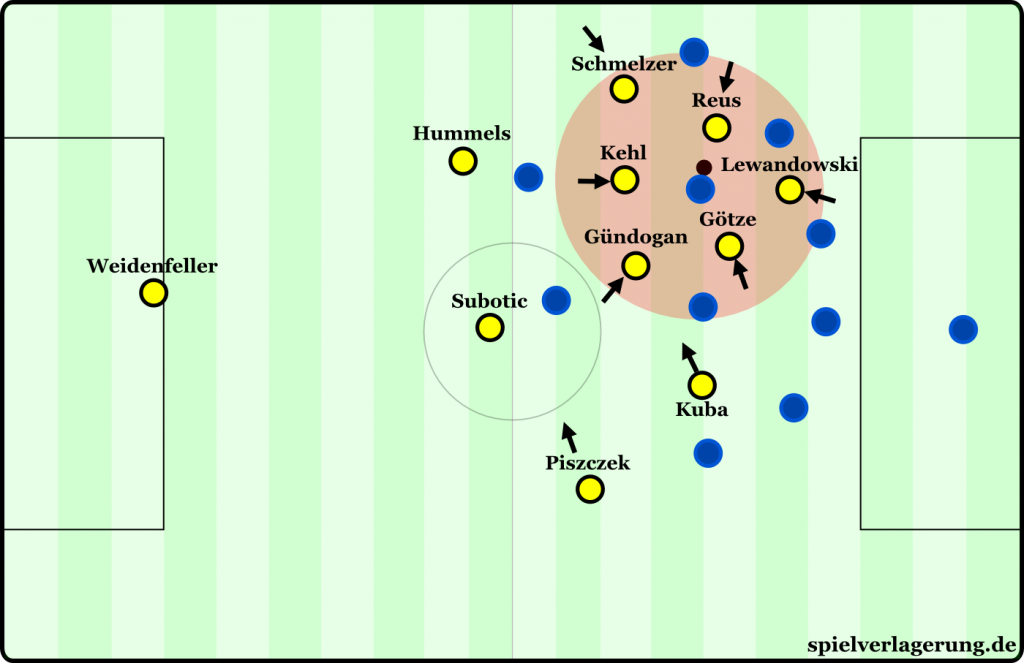

Still, a few teams often are called stand-outs in the application of this specific strategy. Some even see Jürgen Klopp’s BVB as the modern team most focused (and perhaps best) in “Gegenpressing” which is one of the fundamentals of the success and philosophy of his great BVB side. Another coach often connected to this style is obviously Josep Guardiola, whose teams would always try to get the ball back as fast as possible; no matter if Barcelona or Bayern. And the forefather of both in terms of defensive work and counterpress is Arrigo Sacchi, who won back to back European cups 25 years ago.

But obviously there are clear differences between all of these teams in their application of counterpressing – a strategy that has become standard on top level nowadays.

ARRIGO SACCHI: CRUDE, INCONSISTENT BUT CONTEXTUALLY INNOVATIVE

It’s important to remember the context in which Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan became the best team in the world. The football from the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s was clearly different from the 80’s and 90’s. The focus on higher athleticism and more speed did already start in the 60’s and 70’s, visible in the great Dutch teams, but in the 80’s it often seemed as it was the primary focus of many teams – and not only that. Athleticism benefits offensive and defensive actions; but in the 80’s – especially in the Serie A – the focus was obviously on the defense.

In 1978/79 and 1979/80 goals per game already dropped to under 1.9 per game. Most of the seasons in the 80’s stayed between 1.9 and 2.1 goals per game with only 1983/84 and 1989/90 being above this limit. For comparison’s sake: The last two seasons were at 2.7 or above!

In this environment Sacchi started to change things. The at times quite rigid man marking, extreme small numbers of attacking players and dense, deep defense were changed to a 4-4-2 zonal marking structure with aggressive press, an offside trap and more competent possession play. And one aspect of this play was the use of counterpressing when losing the ball.

Back then most teams immediately dropped back after losing the ball; often the strikers just stayed passive and upfront, the others trying to drop in front of the defenders and the defenders not really advancing anyways. Milan at least tried to use counterpressing and stay high although there are clear differences to Pep’s counterpress.

Sacchi’s Milan did not press all the time highly nor did they always counterpress. It very much depended on the match plan. In the legendary European games versus Real for instance they did use counterpressing because the opponent was overmatched, used man marking (thus being forced into a bad structure when winning the ball) and was vulnerable to being pressed.

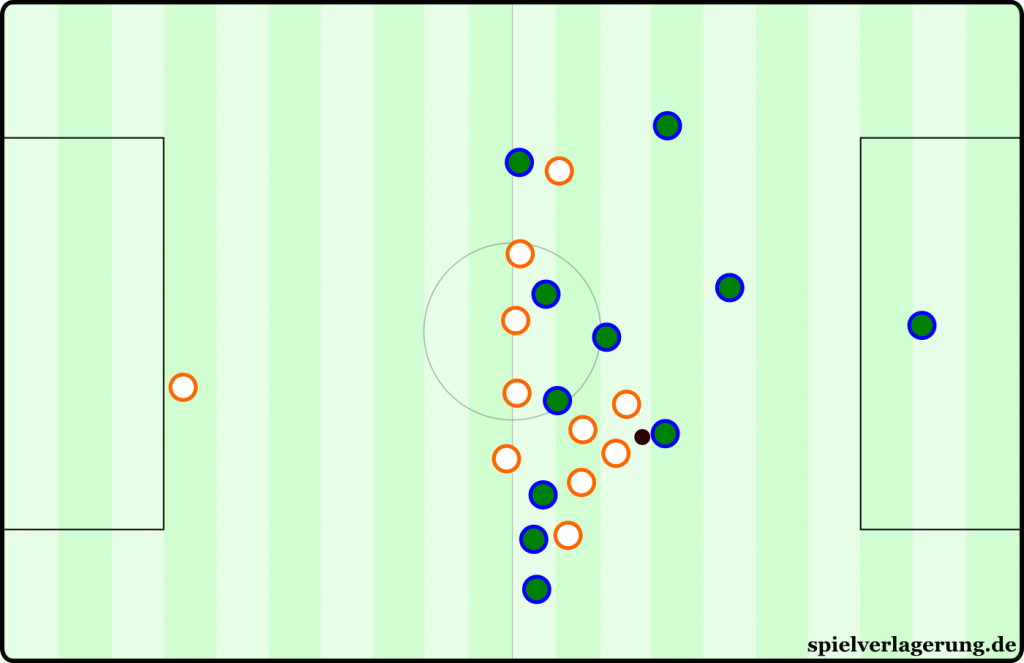

In other games – for instance versus Bayern in the same years – Milan would only counterpress sometimes and often drop deeper immediately to not concede space to the opponent. Because of this, Milan just wasn’t as consistent, fast and collective in their counterpress as their modern counterparts would be – even when they apply it for a game. The players around the ball would sometimes counterpress with the other players dropping deeper again or wait.

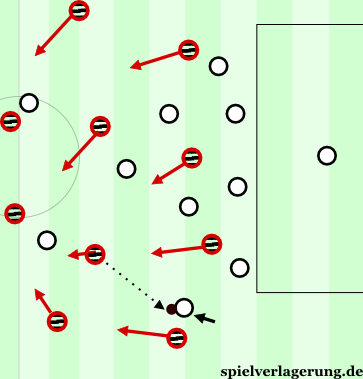

Here Sacchi’s team is immediately dropping collectively to get behind the ball. Goal: Ensure stable defensive shape, then start regular pressing again

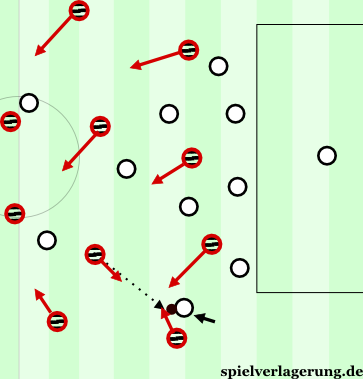

Sacchi’s team counterpresses near the ball, the ball far players are dropping diagonally towards the ball and towards the back. Goal: Stop or prolong the oppositional counter while creating the own defensive shape in the first two lines

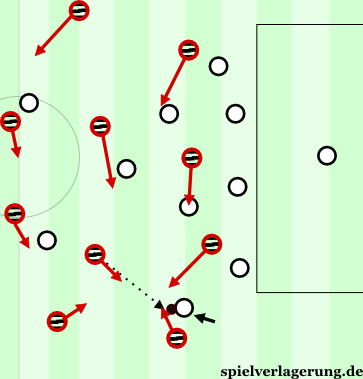

Sacchi’s team collectively counterpresses with all players and attacks towards the ball. Goal: Stop the counter, win the ball, attack again by yourself!

Still, it was existent – but not on the level of Klopp and Guardiola nowadays.

KLOPP AND GUARDIOLA: GREAT APPLICATION WITH DIFFERENT GOALS

Sacchi basically used counterpress as a mean to continue pressing or to prevent counters – which is the main goal, of course. The ball near players would attack, the other drop which would open space – back then this already seemed an offensive tactic, nowadays it’d probably be a somewhat unclean and suboptimal application. Also the players leaving their zone to counterpress would do it individually and not being followed by the other players of their team which again opened gaps. Klopp and Guardiola created a much different structure to Sacchi’s team in counterpress.

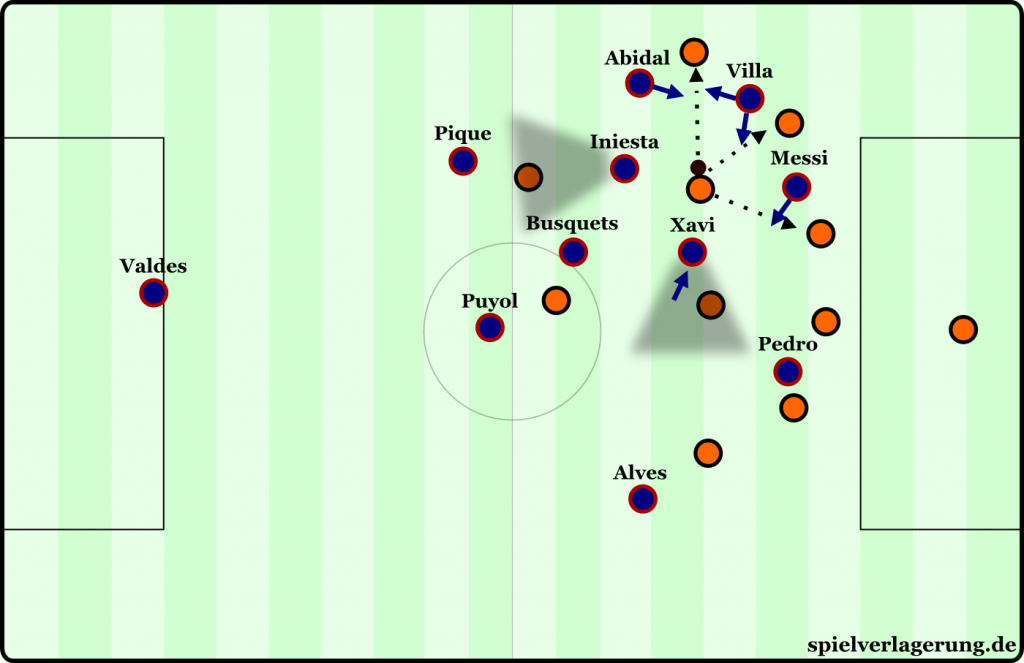

Guardiola’s teams for instance apply Juego De Posición which makes them very well positioned as collective to be able to counterpress. The positioning of the collective and the dynamic within it define how well you’ll be able to counterpress – no one knows this better than Pep Guardiola.

In their press they often try to immediately force the opponents to long balls or intercept their passes. On the other hand they use it every single time when losing the ball in nearly every game. The goal for Guardiola is clear: Don’t allow the opponents to build attacks, don’t let them build up calmly and try to get the ball back as fast and high as possible.

Guardiola’s goal with his counterpress is thus to prevent counters, to prevent a deformation of his attacking shape and to being able to secure the ball. Here lies the big difference to Jürgen Klopp, now coach of Liverpool FC and former CL-finalist and twice German double winner with Borussia Dortmund.

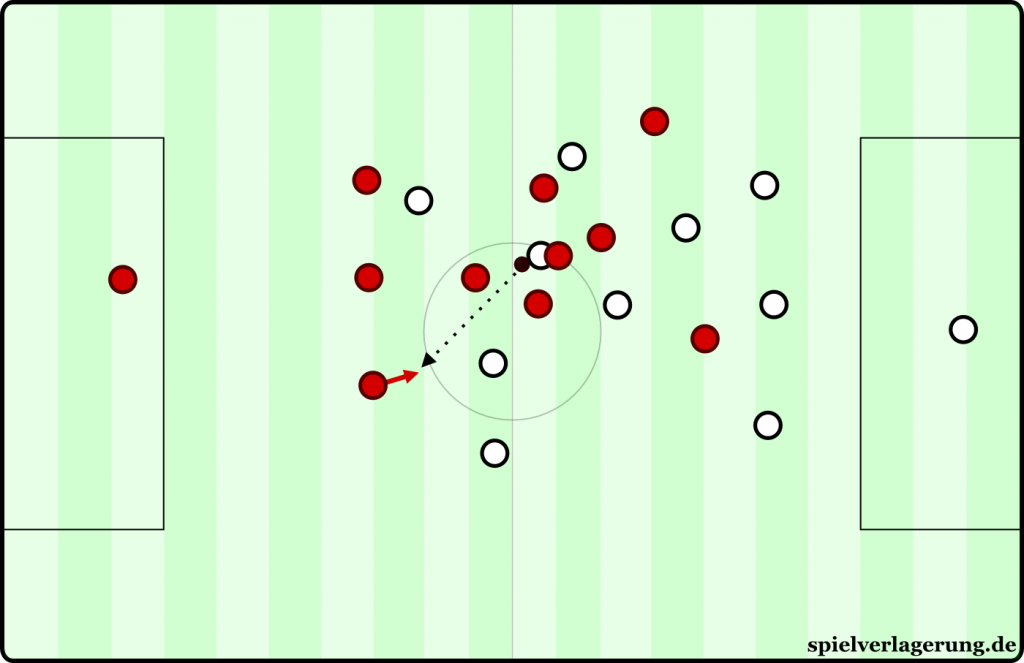

It might be a cultural reason but unlike Guardiola, who sees offensive transition as a mean to transition into the positional structure he wants for organized possession and position play with the ball, Klopp uses the “offensive Umschaltmoment” as attacking mean. For him, counterpressing is the best playmaker and creates the best shots.

The logic is clear: When the opposition tries to counter, they surrender their offensive structure whereas your team is still in it’s offensive structure. If you are able to win the ball at this moment, you’ll find gaps in the oppositional shape to attack them with your attacking players already in the proper positions and orientations.

Here’s where Guardiola and Klopp differ. Of course Klopp also has the goal to prevent a counter and of course Guardiola’s team can counter immediately, too, when necessary, but their primary goal and motivation for the use of counterpressing is different.

This also shows in how the ball is lost; Guardiola’s team often lose it with ground passes in high zones with many players around it and immediately pass back into open deeper space whereas BVB tried to commence their action with an immediate penetrating pass forward or a dribble and often purposefully induced counterpress by a long ball forward.

Still, both – Klopp and Guardiola – heaved counterpress on a new level since 2008; together. Their teams counterpressed more consistently, collectively and intensely than any other team since the Netherlands 1974 and perhaps even more organized with more details and additional motivations.

* Rene Maric is a football analyst on Spielverlagerung.de

BUSCADOR DE CATEGORÍAS

BUSCADOR POR MES

ÚLTIMOS TWEETS

Tweets por @martiperarnauSÍGUENOS EN FACEBOOK