Pressing, Counterpressing and Counterattacking

[Definition|Philosophy|Strategy|Tactics|Techniques|Psychology]

Pressing, counterpressing, and counterattacking are three very popular concepts that are associated with the most exciting and dominant teams in modern football. Pressing and counterattacking are perhaps the more “classic” ideas in football tactics, while counterpressing is a buzzword which has become quite popular over the last five to six years – despite having existed for decades. But what do these terms really mean and why are they so important to modern football?

PRESSING

Pressing can be defined as creating tension with the intention of getting the ball back. This is sometimes confused with pressure, which is the tension itself. Pressing is the application of the pressure with a specific intent. Every movement on the pitch creates some sort of pressure or tension somewhere on the field. Without any pressure or tension the opponent could walk straight upfield and shoot on goal every time.

So, what distinguishes pressing from a defense that doesn’t press? Intent. When pressing, a team is actively trying to win the ball back through pressuring the opponent and by moving out of or within its formation. When a team isn’t attempting to win the ball back, but to contain the opponent’s offense – then that team’s intention is to defend the goal by stopping the opponent from creating chances without taking the ball from them.

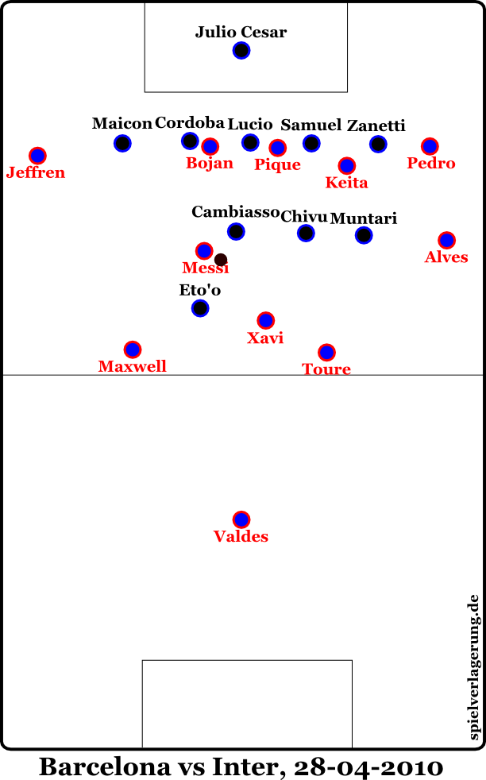

For example, Mourinho’s Inter Milan in the second leg of the Champion’s League semi-finals against Guardiola’s Barcelona didn’t want to win the ball. They only ever had the ball because they had to – because if Barcelona lost the ball trying to create a chance it meant that possession had to change into Inter’s hands. Mourinho’s men immediately rid themselves of the ball in transition in order to avoid any sort of disorganization which would stem from being counterpressed or losing the ball after a counterattack. Mourinho said after the game that he didn’t want his side to have the ball:

“We didn’t want the ball because when Barcelona press and win the ball back, we lose our position – I never want to lose position on the pitch so I didn’t want us to have the ball, we gave it away, I told my players that we could let the ball help us win and that we had to be compact, closing spaces.”

Pressure is one characteristic of the atmosphere around the ball which creates conditions in which the opponent can no longer properly control the ball and is ultimately forced to lose possession. Pressure forces an action to occur rather than allowing it to occur based on the will of the opponents. When an action is forced in a pressured atmosphere, every aspect of that action is made more difficult. An action consists of both a decision and the execution of that decision – if these two aspects can be manipulated correctly, the opponent will lose the ball.

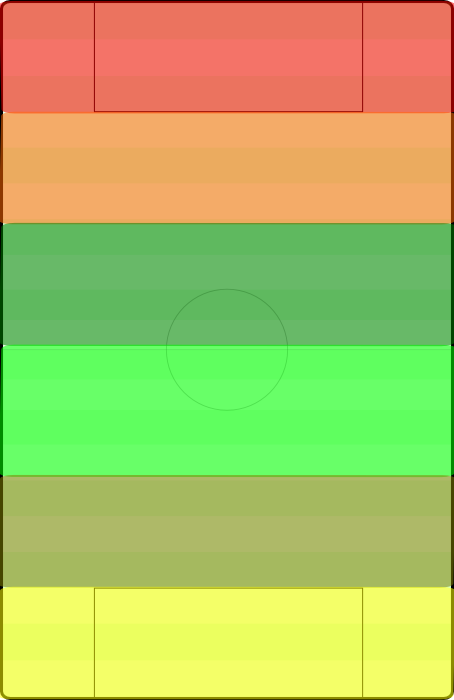

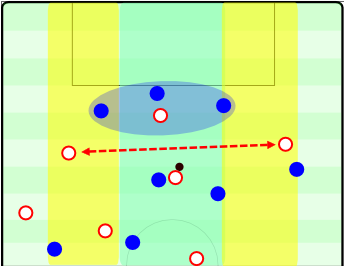

The red/orange third is the attacking third, the light/dark green is midfield, and the yellow/olive is defensive. The colors within them represent the split into high and deep zones (for example, red = high attacking press, orange = low attacking press.)

The German football association’s model for distinguishing the different types of pressing is quite good. The field is split into three horizontal thirds – the attacking, midfield, and defending thirds. Attacking pressing occurs in the attacking third, midfield pressing occurs in the midfield third, and defensive pressing occurs in (you guessed it!) the defensive third. However, the German FA divides the thirds even further by assigning each one a high and deep zone.

This means it’s possible to have high-attacking pressing, deep-attacking pressing, high-midfield pressing, deep-midfield pressing, high-defensive pressing, and deep-defensive pressing. A good way to think of it is to just split each third in half horizontally and call the top half high and the bottom half deep.

The most fundamental component to pressing is being able to press. In other words, you have to establish access to the ball in order to be able to exert pressure upon it. This concept goes hand in hand with the preparation for pressing, meaning that every action must be prepared for (in this sense positionally, but it can apply to psychology or other aspects of football) – including the pressing itself. If a pressing action is prepared for properly then the pressing team will have proper access to the ball.

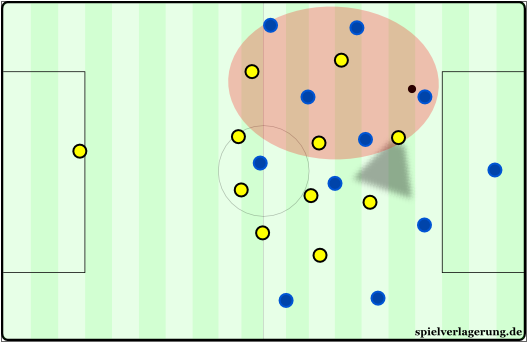

Poor preparation for a pressing moment.

Poor preparation leads to a poor press and access.

If there is access to the ball the entire dynamic changes in comparison to when there is no access. When a team is able to pressure the ball it allows the rest of the team in the deeper layers to push towards the ball and leave space on the far side of the field open. If a team played with a high defensive line but didn’t pressure the ball they would concede a lot of goals because of allowing long passes into the space behind the defenders. If a team which played very horizontally compact didn’t pressure the ball they would have a very hard time defending because every switch of the ball would expose the underloaded far side.

If there is no access to the ball then the defensive team must answer the obvious question: How do we re-establish access without being exposed? There are multiple ways to do this. The most common way is to ignore the ball as a reference point and collectively move towards the space where the ball will eventually arrive. In other words, drop deeper and more centrally to protect the space near the goal and wait to force the ball backwards or wide and away – the space behind the defense and in front of the goalkeeper decreases as the ball moves forward and the defense moves backwards. Another option is to move collectively towards the ball and play with the offside rule. If prepared and timed correctly this can be an extremely valuable way to win the ball back even without access to the ball.

Preparing for the press means moving into the proper positions to be able to press according to the team’s strategy. It’s also possible to prepare the offensive team for the defensive team’s press. It’s quite common to see a defense “condition” the play of the offense in a certain way in order to move them into an area the defense is seeking to press.

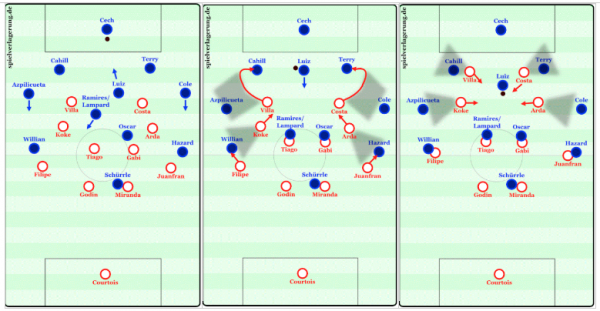

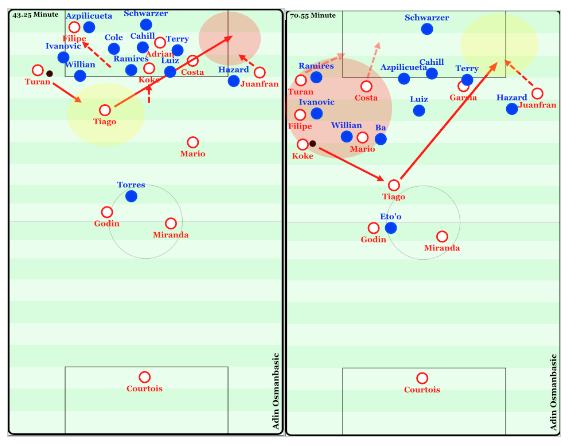

Atletico preparing Chelsea for a pressing trap in the center of the field.

Above is a variation to preparing the opponent for the press. Atletico Madrid seek to move the opponent into the center of the field in order to isolate him from his teammates and then close the pressing trap on him. The players move in specific routes and block the outside passing lanes in order to encourage the opponent to move into the center of the field.

Once the opponent is isolated from his teammates and has no escape route, the team can move towards the ball collectively and win it in a good area which would likely result in a great counter attack. Pressing traps can vary as well – aspects of the trap include where the trap is set up to isolate the opponent, how many players participate in the trap, the type of pressing when closing the trap, how the opponent is isolated, when the trap is set, and more.

In the above example, Atletico Madrid were quite active as they moved out of their shape to start and baited the opponent into the center. Preparation varies depending on if its dynamic or static and which game phase or game state it is in.

So what are the triggers to begin a press once in position to do so? They normally depend on aspects like field of view, control of the ball, ability of the player, connectivity of the opponent, or the nature of the pass. If a player isn’t facing in the direction of his passing options then it is extremely difficult to escape a press, therefore the team should press before the player can re-orient himself.

The ball is much easier to take from an opponent who controls it poorly. A team can collectively press the ball at the moment it’s miscontrolled because it would take time to re-establish control of the ball. This plays a part in the “opponent’s ability” as well. If the player is very poor at making decisions and controlling the ball it would be logical to put that player under immense pressure as soon as he’s about to receive it. Most players are taught to press the opponent “as the ball is traveling” because the scene cannot change dramatically within the time the presser leaves his position as the ball is moving between players.

The ball cannot dynamically change directions in the middle of its route between players (unless there is some crazy spin on the ball, which would be visible and anticipated by the players) so it is an optimal time to press the destination point of the ball. If the presser decided to leave his position while it is under the control of the opponent player (without the following layers of the press to protect the vacated space and cover him) then the ball could change direction quite easily as the opponent can simply dribble and exploit the movement of the presser.

When the defending team goes to press can also depend on which section of the field they set up their block and where they seek to isolate the ball. The press can also vary on which part of the team begins the press, which direction the team moves, and when the press stops.

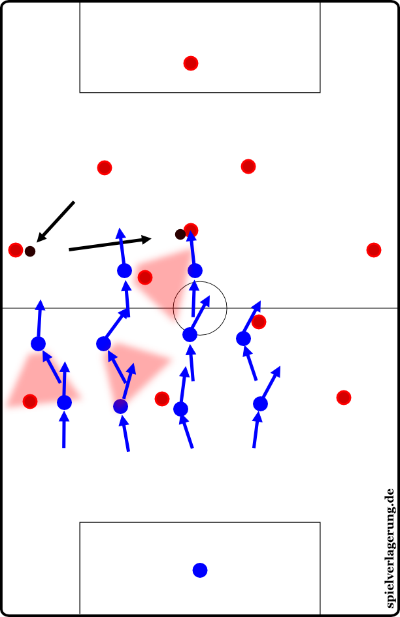

An example of a team pressing an opponent towards the center and then towards the sidelines once the ball has moved there.

If the team is seeking to press high up the field and towards the center, it’s possible for the wingers to begin the press with arcing runs towards the central defenders while blocking any passing options into wide areas. If the team seeks to press from the midfield towards the flanks it’s possible for the winger and fullback to begin the press against the touchline.

The pressure usually stops when the ball is won, when access to the ball is lost (due to being dribbled, failing a tackle, being overloaded, etc.), or the ball is forced deeper than the pressing team is willing to move. It’s also possible to stop pressing once the ball is forced into an area which isn’t necessarily deep, but which the team feels comfortable leaving unpressured, such as the flanks in the midfield. For example, in certain situations Barcelona have forced the ball wide and then just focused on the center while just containing the opponent in wide areas and not allowing penetration.

Similarly, the direction of the press can vary depending on the compactness of the team – horizontally, vertically, and diagonally. Within that compactness there are more specific forms of pressing like backwards pressing and pressing within one’s own shape. Diagonal pressing refers specifically to a team moving directly towards the ball and “cutting the corners” of your formation as they are the least valuable areas and they are furthest away from the ball. Basically, if the ball is in the center of the field the team will collapse diagonally towards it – if the ball is with the opponent fullback the team will collectively move towards it in a diagonal fashion.

Horizontal and vertical pressing is basically when the team (or a section of the team) moves collectively towards the ball in a purely horizontal or vertical fashion – which is more theoretical. When looking at the concept of backwards pressing, it is referring to when a player presses the ball once it has already past his position on the field. For example, if the ball moves past the two strikers in a 4-4-2 formation and in front of the midfield 4, if the two strikers move backwards and press the opposition from behind they are performing backwards pressing (which doesn’t occur very often even in big leagues like the EPL that typically lack compactness – which might also be a psychological point, because players don’t want to backwards press if they don’t have support in the immediate vicinity).

Pressing is not always “collective” either, the collective positional structure is made up of individual players in specific positions and specific phases. Some players might still be focusing on “defensive organization” while others are already pressing together. Also, one player could be man marking while others are performing zonal marking. Not all players are always in the same phase or moving in a collective fashion – which can lead to some very complex pressing systems.

Not all defensive movements are the same either. The types of defense I will describe are variants of zonal and man-marking. Along with that, you can take the variations of pressing movements I write about in the counterpressing section of this piece as variations of pressing too. It’s important to remember that pressing is usually a mix of these variations instead of being purely one type of pressing during the match.

Rigid Man Marking

In “rigid man marking” each player chooses an opposing player and presses him specifically, following the opponent wherever they go. This is easy to do for the players as it doesn’t require much thinking. The idea is to have constant access to each opponent at all times throughout the game and therefore put huge pressure upon the opponent while blocking their options.

The weaknesses lie in the fact that each opponent is followed by a player. This puts the pressing player in a reactionary role as they must follow the opponent’s movements – therefore losing control of his own movements. The opponent can drag his opponent away from important areas to open space, he can switch positions with other opponents to confuse the pressing team and disrupt their structure, and if the opponent is skilled he can beat the pressing player and potentially create overloads all over the field.

Flexible Man Marking

This type of man marking is similar to the previous variant except that players seek to switch players off to each other whenever possible in order to avoid being dragged away from important areas or avoid confusion when players switch positions during a press. An obvious problem here is in the moment of the transfer. When transferring an opponent from one presser to another there are two pressing players on one opponent, meaning there is an open player elsewhere.

Space Oriented Man Marking

In this variant the pressing players are focused on protecting a specific space around their position, and if any opponent moves into this space the pressing player begins to man mark the opponent. Once the opponent leaves the designated space the player returns to his position and protects his zone. The logic behind this variant is that any opponent who is near the ball should be pressed while the rest of the team seeks to close available spaces.

When a player leaves his position to man mark the rest of the team can collectively move towards the opened space to close up any holes – though this does create space on the far side of the field. A weakness of this variant is that the player that leaves his position can easily be manipulated and bypassed thus creating overloads higher up the field for the opponent.

Position Oriented Zonal Marking

In this type of zonal defense, players seek to remain in their positions in relation to their teammates and shift towards the ball. The idea behind this type of zonal marking is that there is no need to directly pressure the opponent or the ball when the team can control the space around the ball by shifting towards it in its block.

Because this type of marking is oriented specifically to one’s teammates the compactness of the team is maintained throughout the block – though it does require a lot of running to close the open space if the opponent seeks only to circulate the ball in safe positions. If the ball is played into a tight near-side area (created by the block shifting towards the ball) it is pressed and the opponent is in a very difficult situation. As you can tell, this form of pressing the ball is a bit more passive in comparison to others because the team just shifts towards the ball and waits for the opportunity to press instead of actively seeking out the opportunity to press.

Man Oriented Zonal Marking

This zonal marking is oriented to the opponent and the pressing players seek to cover their respective zones while moving closer to a player which may be within the zone. This is different to the Space Oriented Man Marking because in that variant the players will focus on defending their respective zones but will aggressively man mark any opponent who enters their space.

Space Oriented Zonal Marking

This variant is focused upon congesting the available playing space around the ball. The team seeks to overload the space near the ball in order to put pressure on the opponent and limit his options. The key to making this form of pressing successful is making sure there is access to the opponent and the ball player is put under pressure.

If the team just shifts towards the space around the ball without putting any access or pressure on the opponent – then they will most likely fail as the opponent can just circulate the ball safely and easily manipulate the team’s aggressive shifting by switching the ball and attacking the open side. Access is the key to any press – particularly one which aims to trap an opponent in a pressured area while vacating the far side of the field.

Option Oriented Zonal Marking

The main point of reference for this type of defense is the ball itself. Where could the ball go? Which is the best way to prevent the ball from hurting us in a specific situation? The players on the team move differently from each other – they focus mainly on flexible movements to prevent the progression of the ball based upon its positioning. This requires a great deal of intelligence and coordination from the pressing players as it can be a huge mix of man marking, zonal marking, blocking passing lanes with cover shadows, etc. If done incorrectly it is possible for a large amount of space to open up in the defensive shape.

To see more in-depth pieces on Man and Zonal Marking look at these articles from Spielverlagerung: Man Coverage / Man-to-man-Marking and Zonal Marking / Zonal Coverage.

Porto players blocking the passing lanes into the Bayern midfielders. Notice the space between the midfield and defense for Porto!

Focusing upon the passing lanes while pressing is an interesting tactic. In basketball this is called ‘fronting.’ The basic idea is that it is better to mark the possibility of the ball reaching a specific destination rather than the destination itself. Would you rather man mark Lionel Messi and let him receive the ball or would you rather mark the passing lane into Lionel Messi and prevent him from ever receiving the ball? This idea is used quite frequently in basketball and contributed to some of Michael Jordan’s least impactful games when he was defended intelligently in this way.

Here is a video of Payton guarding Jordan and fronting him frequently.

It basically forces the opponent to choose a different pass option and move away from the lane that is being blocked. Porto did this against Bayern’s central midfielders when they were higher up the field. When Bayern’s players dropped deeper they simply stayed oriented towards them but goal-side of the ball.

Here is a video which shows a few examples of what happens when a player tries to front in too much space or with no support.

It would be unstable to front a player who drops extremely deep as another player could just move into the vacated space or the player who is being covered could utilize the large amount of space to escape the cover shadow. Bayern focused on longer passes over the opponent midfield and into overloads before crossing in the second leg comeback.

This was more successful because in the first leg Bayern attempted to play through the Porto midfield which was blocking passing lanes – but in the second leg they focused upon moving directly into the space (which was huge due to the midfielders positioning themselves higher up to block passes) behind the Porto midfield by bypassing them completely.

When there is a smaller amount of space it is easier to cover a passing lane because the movement of the covered player is limited – therefore the angle from the ball to the player is much easier to move with (as the ball is extremely dynamic in its positioning for the most part, it’s important that its destination point doesn’t have the opportunity to be as dynamic) and lobbed passes into the space are less successful.

This is why the “fronting” done in basketball happens more often in the “low post” which is closer to the basket and the baseline where there is less space rather than near half court where there is a lot of space to move in. Another difficult aspect when looking at fronting in large amounts of space is that there isn’t as much direct contact between the players so blocking the passing lane is even more difficult as the opponent has free movements with nobody physically disrupting him and the pressing player is put into a reactive role.

Cover shadows and specific running paths which block passing lanes happen very frequently when pressing. Guardiola’s principle of defending two players at once by defending the space in between them applies here. There are various running paths that can be taken during a press and various ways to utilize cover shadows – but the idea behind it remains the same; the opponent’s decisions can be more easily manipulated when their ability to make “other decisions” is decreased. By reducing their options a team can actively change the possessing team’s structure and passing patterns.

This leads into how pressing allows a team to control the rhythm of the game. In modern football, defense is normally more dominant than the offense in regards to thinking structure. Offenses are usually in a “reactive” role as they don’t seek to change the defense’s structure. Rather, they react to what the defense is doing and attempt to score with that reactive offensive thinking structure.” As a defense marks their zones they gain some control over the situation – they are no longer following the opponent, but they are defending their space and the opponent must play against them rather than controlling the defender’s movements.

An example of a half back moving forward and forcing the opponent to change.

To find some articles on the “advancing halfback” and David Alaba’s role as a left halfback look here: Der vertikale oder vorstoßende zentrale Abwehrspieler and Aspektanalyse: David Alaba, der Halbraumlibero.

Most offenses search for how they can go around or through a defense, but don’t look to change the structure of the defense itself in favor of the offense. An example of this “proactive” form of attack is Pep Guardiola’s teams – specifically Alaba’s role as a “half-space libero” where he moves forward from the halfback role and can force the opponent into a 4-4-2. An “active” offense is one that would resemble the more rigid attacks of Bielsa or Van Gaal – one which plays in its way regardless of what the defense is doing.

A “passive” offense would resemble Mourinho’s Inter in 2010 vs. Barcelona in the second leg where it doesn’t seek to do anything. One extra category could be added called “ignorant” in which the team simply ignores the opponent and tries to play, and even further layers could be distinguished within these thinking structures such as “passive aggressive” – though all of these thinking structures require a separate and more in-depth analysis for another theory article.

This defense definitely thinks differently in comparison to the previous example with Atletico Madrid, no?

Defenses have similar thinking structures too. They behave in similar ways to the offensive thinking structures, meaning that a proactive defense would seek to change the structure and movement of the opponent. A team which presses correctly could force the opposition to alter their positioning in order to continue playing – which disrupts the opponent’s harmony and dynamic. If the positional structure of the offense is forced to change, then the combinations to escape pressure will have a different structure as well – usually forcing a weaker structure. In this way, a defense can “attack” the possessing team. Therefore, some coaches do not believe in the “phases of the game,” which I will elaborate upon later in the piece.

There can be a special psychological effect that comes with aggressive pressing or counterpressing as well. After a team has pressed the ball a few times, the possessing team will begin to expect the press. They make decisions as if they are being pressed even if they aren’t “truly” being pressed any longer – in this way a “false press” can evolve and a team can merely display the beginning characteristics of a high press and force the possessing team into poor decisions. This both saves energy and allows one team to control the other. It can lead to “rhythmic pressing,” where a team spends portions of the game pressing intensely and other portions in a “resting press” or a “false press” – which has its own specific advantages.

The act of pressing an opposing team and their space to play takes away options by guiding them away from the pressured areas. Depending on the options left to the player with the ball it can also increase the difficulty of executing a decision. The time it takes to perform an action is decreased in both physical and mental ways. The “fear” or anticipation of a press happening can force the player to play as if some decisions are already unavailable for him before they truly are.

Finally, the different aspects within a compact press should be differentiated and evaluated. Tom Payne at Spielverlagerung wrote an in-depth tactical theory piece on the subject for us. It is possible to differentiate the aspects of compactness into space, tactic, dynamic, and synergistic compactness (with access of course). Spatial compactness refers specifically to being compact within one’s own shape – in other words, there isn’t much space within the block of the team.

Tactical compactness means that within the team’s block the defense doesn’t open various possibilities for the opponent play to within it. Dynamic compactness means that within the block the team is positioned to more easily anticipate the opposition’s actions in order to pressure them quickly.

Finally, synergistic compactness (or staggered compactness) means that within the positional structure of the defensive block there is cover and layers to any movement, trigger, or action that is performed by the block. Along with access to the ball, these are all aspects which you could find in a compact team, but it’s important to differentiate these deeper layers and understand them in order to use them better. In the end, a mixture of all these aspects is what makes compactness successful.

Some things to think about in regards to pressing are: in option oriented zonal marking, movements which are in the opposite direction of the block’s collective movement are underrated and have interesting effects. The idea that not all players are in the same game state or phase on a physical or mental level is interesting as well and opens up a lot of possibilities when looking at specific positional structures and how to achieve them.

COUNTERPRESSING

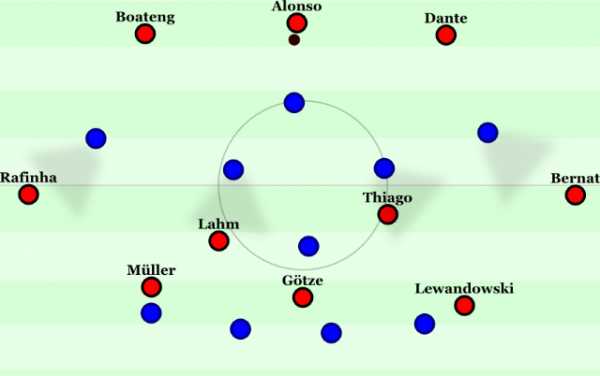

Counterpressing is a concept which has largely attributed to the success of teams such as Jürgen Klopp’s Borussia Dortmund, Jupp Heynckes’ Bayern Munich, as well as Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona and Bayern Munich. So what is counterpressing? And is every counterpressing scheme the same?

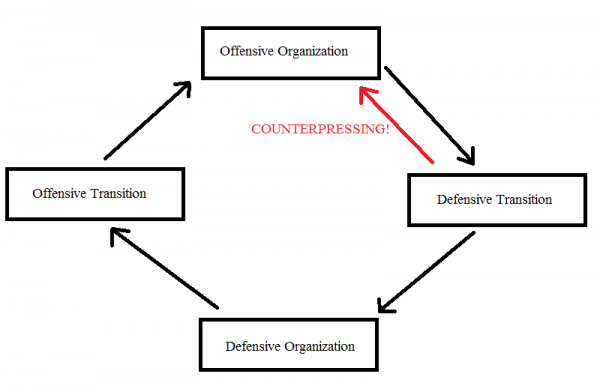

The effects of counterpressing on the traditional 4 phase cycle (yes, I did use MS Paint for this).

Counterpressing can be defined as pressing the ball in transition from offense to defense – attempting to move the cycle of the “phases of play” in the opposite direction. The cycle of the game moves in the fashion shown in the above graphic – but what if you could move from offensive organization to defensive transition and immediately back into offensive organization? This “match control” is a main characteristic of counterpressing. It allows you to skip the defensive organization phase entirely if done correctly.

Guardiola has said that his Barcelona team were the “worst defensive team in the world,” so he liked to avoid defending against the ball as much as possible. The cycle is quite flexible and can be manipulated in many ways throughout a football match – with some teams seeking to stay within only a few phases of the cycle and others playing throughout all of the phases. For example, a team caught in a “chaos pressing” matchup could be playing in offensive and defensive transitions constantly – never truly settling into any “organization.” It’s possible to catch two strong counterpressing teams in these types of exchanges throughout games. It could also be a peek into the future of football – who will control the chaos better?

Counterpressing not only plays a large role in controlling the rhythm of the game and stabilizing the defense, it also plays a big role in play-making. If the ball is won successfully in defensive transition that means the opponent was in offensive transition and moving into an attack. Because the opponent was moving into a counterattack (which means they were spreading out and running up the field) when they lose the ball they are unorganized and exposed in regards to controlling the offensive transition of the ball-winners. Schweinsteiger admired how Spain prepare for defense while in possession here:

“If you look at the ideal example, Barcelona or Spain, you can see how good their defenders are at setting up, even while they still have possession. That is perfect defending. The teams that defend well in this tournament will go far. In many situations when you are attacking, you already have to start thinking about what happens once the ball is lost. As a defensive player, you already have to watch the opposing attackers and ask yourself what could happen when the ball is lost.”

– Bastian Schweinsteiger

Preparation is an important aspect of both counterpressing and pressing. In order to properly pressure the ball, the players must be positioned in the correct areas before the ball is lost. It requires concentration as well as the ability to quickly switch mentality from attack to defense.

Pep Guardiola has a famous “15 pass rule” in which the main purpose is to make sure his players have the time to move into their appropriate positions within the team’s structure before beginning the attack. The reason the players must take up these positions is not only to prepare to attack but to defend. If the players are positioned properly they will be able to press better in defensive transition. The players cannot focus completely on offense at all times, they must be thinking about what will happen if they were to lose the ball and position themselves accordingly.

Many times teams will move forward “too early” in regards to how many players they have in forward positions in relation to the opponents. This results in an inability to control the transitions through pressing. Therefore, the team who is poorly positioned to pressure when the ball is lost must react to how the opponent is attacking rather than determining how the opponent will play by pressuring them. This ultimately results in a lack of game control.

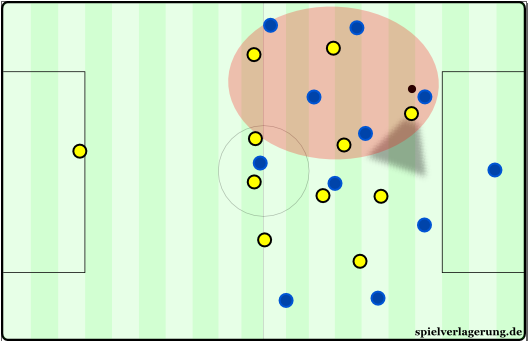

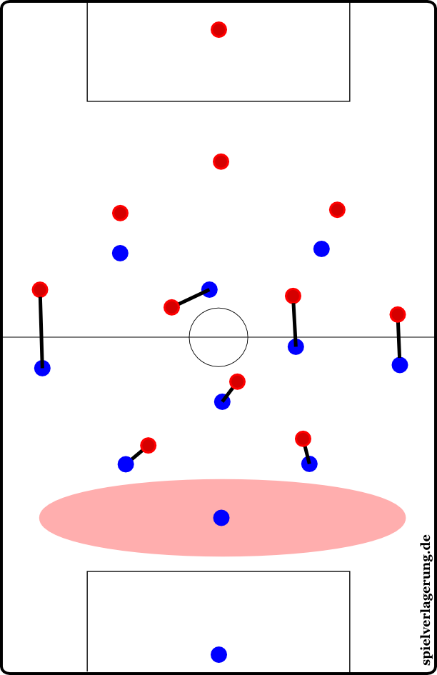

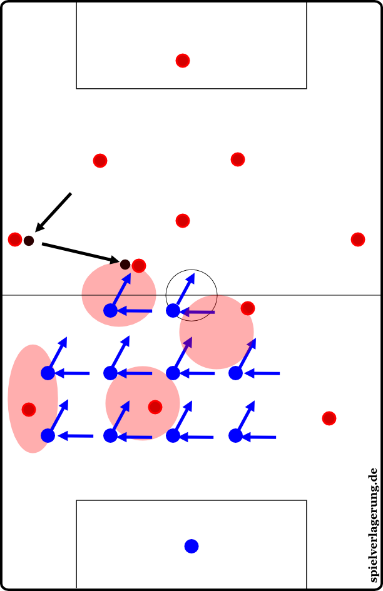

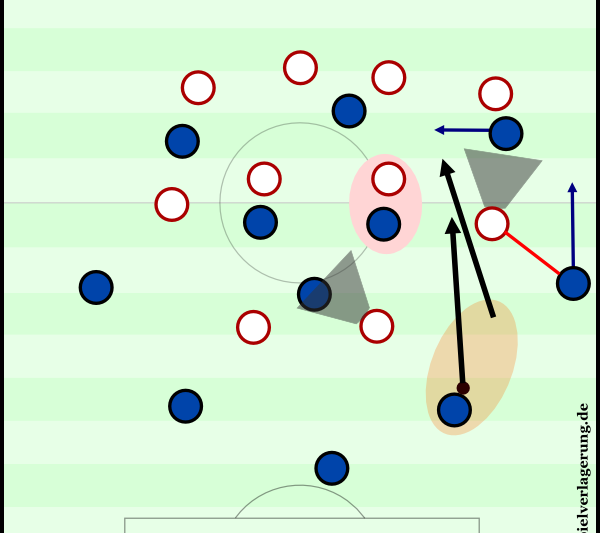

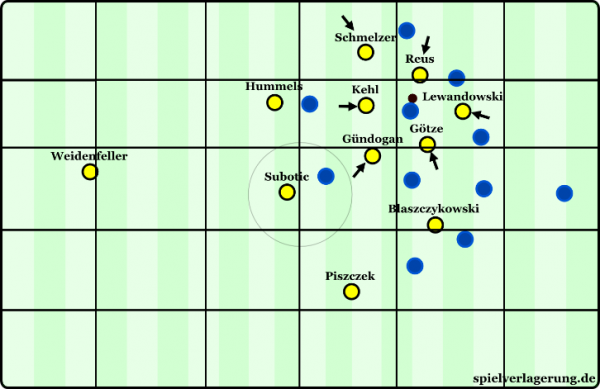

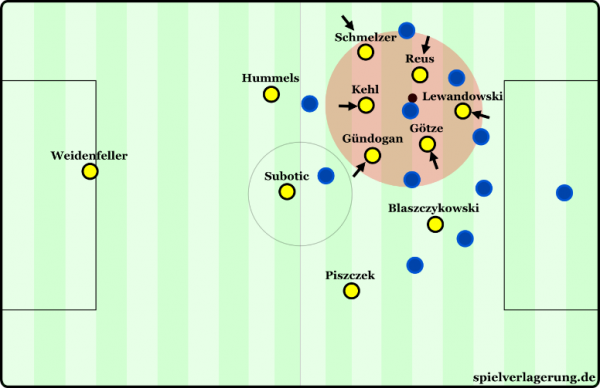

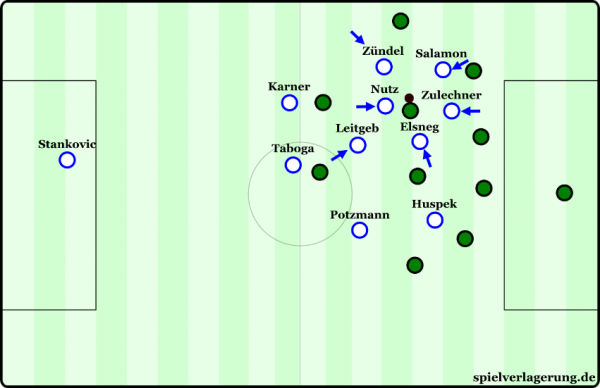

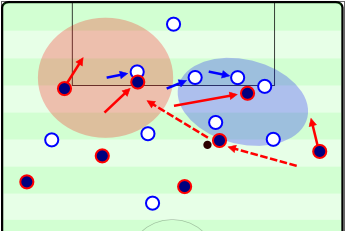

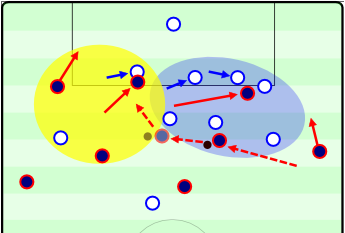

Dortmund trying to occupy a small area of the field while remain distant from each other during counterpressing.

A basic guideline for positioning could be for the players to seek to occupy smaller areas of the field in a compact manner while remaining as far from each other as possible (and maintaining connection) within that small area. It’s also important to consider the value of the center of the field while pressing. When the opponent wins the ball they can be forced away from the center of the field and towards the touchline or even backwards – limiting his space, ability to turn, and reducing his options. This causes the transition to take longer or the ball to be won back, and if the transition takes longer the defense can reorganize more easily.

A team which players extremely wide and focuses on playing through the flanks would struggle to counterpress properly as they aren’t compact. At the same time – a team which plays extremely narrow wouldn’t be able to counterpress properly because they wouldn’t control a large enough area of the field. It is all about balancing the positional structure in regards to the opponent’s defense. A coach can decide where the team should be narrow and where it should be wide, maybe depending on where the opponent’s best player plays.

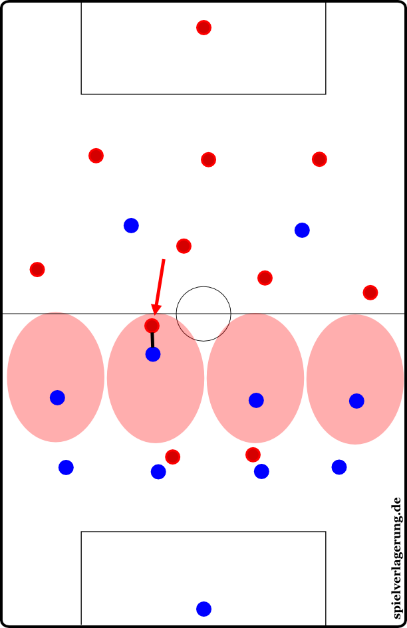

Just like a normal press has specific differences, counterpressing does as well. The defensive transition looks similar to a team which sits in a compact block and shifts towards the ball. Though when transitioning from attack into defense, teams are in an “offensive structure,” which can be described by crazier numbers in regards to formations, such as 2-3-2-3. But how exactly does the team try to win the ball back in these moments?

Space-oriented

This category is what Jurgen Klopp’s Dortmund would fall under. This method is focused on congesting the available space for the opponent. When the players press the space around the ball the opponent will be cut off from his teammates, pressured, and won’t have any room to play. The team seeks to move in a compact fashion towards the ball and focus on the space around the ball instead of specific opponents or passing lanes as the high number of players in the space around the ball naturally cut off the opponent’s teammates and passing lanes.

This type of pressing suffocates the opponent’s space and the players can move closer and closer to the ball before taking it away, forcing a turnover from a short pass attempt, or steering the ball into a disadvantageous area. This is similar to a very compact zonal defense shifting towards the ball – they are focused congesting space while moving towards the ball, but they also make sure they are connected to the opponent.

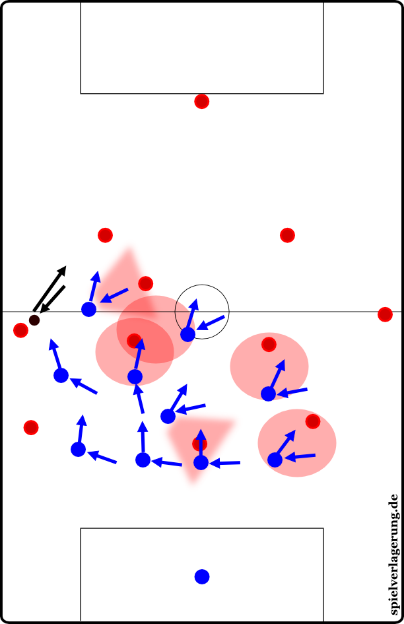

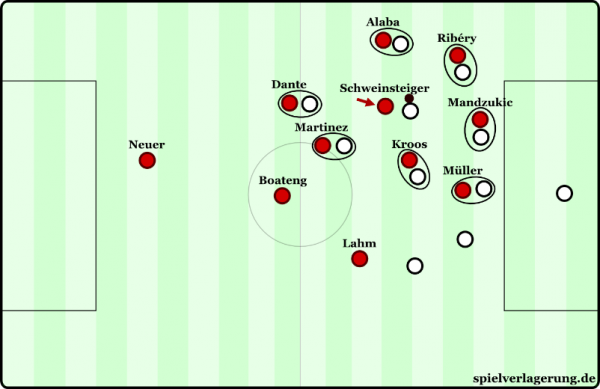

Man-oriented

Heynckes’ Bayern often used this method. The focus here is on pressing the ball with one or two players while the other players focus upon any access points the opponent on the ball may have by moving into a man-marking scheme in the surrounding layers of pressure. The advantage of man-marking is that the defenders will always have access to the opponent – meaning they can directly challenge for the ball every time.

The presser of the ball must be careful not to be beaten by the dribble as this form of pressing is more oriented towards direct challenges. Normally, the ball presser will try to force an action, but if he can win the ball that’s even better. In contrast to space-oriented counterpressing, this pressure allows more breathing room for passes but it leads to many more challenges and tackles. This fit Heynckes’ team well as they had players who were excellent in challenging for the ball.

The danger lies in the fact that man-marking can easily be manipulated by dragging the pressers around and destroying the stability of the press. It can also be tough if the opponent has excellent 1 vs. 1 players and players who are excellent in tight spaces.

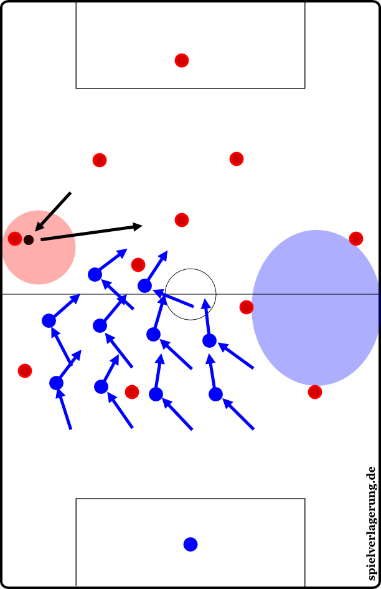

Passing lane-oriented

Pep Guardiola’s teams fall under this category. This type of Counterpressing is primarily focused upon coaxing the opponent into playing a pass into a seemingly open lane before intercepting the ball. The players immediately move towards the ball and block certain passing lanes while leaving others open – this baits the ball player into trying to play a pass to his teammate, but the passing lane is then attacked by one or more players for the interception. The team usually seeks to force the ball into areas less strategically important areas like the sidelines where the opponent is further from the goal and space is congested.

Sometimes they will block all of the passing lanes and move towards the opponent in order to force a long pass or force a pass backwards – or, alternatively, give up the ball.

Ball-oriented

If you’re looking for more articles dedicated specifically to counterpressing we have two here: Counter- or Gegenpressing and Counterpressing variations.

The Dutch team of the 70s could fall under this category. This pressing is focusing solely on the ball. All the players in the surrounding area press the ball immediately once its lost without focusing on the ball-player’s options. This wins the ball by exerting huge amounts of pressure on the ball carrier and whoever he might pass it to. This is dangerous if the player on the ball is a good dribbler and can beat a player to lift his head up to open options for an escape pass – which the pack of pressers wouldn’t be able to follow at the same speed the ball is moving.

Pressing takes dynamic movement, good anticipation, and intelligent execution. This is why most of the best dribblers in the world are also good at pressing the ball, e.g. Lionel Messi. When Messi is actually working hard on defense he is quite an impressive presser of the ball who can perform many different actions.

One specific action while pressing is to deliberately run past the opponent, this would mean the opponent would not be slowed down, but the pace of play will be quickened. The pressing player will likely miss the ball due to not seeking to “sit down” and establish a distance to the ball and control his speed when engaging the ball player. When moving full speed towards the opponent it is quite easy for the player on the ball to move past the presser, but the presser’s intention isn’t to win the ball – he only wants to force the opponent into a quick movement and get his head down.

After the player on the ball makes his quick movement it is easy for the rest of the pressing players to read his next move and recover the ball. The player who ran “through” the opponent is then an immediate and direct option for transition as he’s moved past the opponent and into open space up the field.

Counterpressing can vary from team to team based upon where a team will look to do it (if they don’t do it everywhere), how many players they use to do it, and how long they seek to do it. The 5-6 second rule made famous by Guardiola’s Barcelona is one example of a team which had a specific timeframe for their pressure – if the ball wasn’t won back within 5-6 seconds of having lost it the players move into their defensive block. Some interesting variations of counterpressing could arise when studying the effect of time on counterpressing situations and how it affects positional structures.

COUNTERATTACKING

Finally, we have Counterattacking. This is a term most people who watch football are more familiar with – as the term has existed for ages in various types of sports, games and combat. Counterattacks can be defined as attacking in transition from defense to offense. This is different than transitioning with the intent to restart a deep circulation of the ball. Once again, the intent of the team is really the key to all three of these concepts.

The idea behind the counterattack is take advantage of the fact that the opponent is in the transition phase. If one team is transitioning from defense to attack, the other team is transitioning from attack to defense. This means that the team which is transitioning from attack to defense most likely isn’t in a suitable positional structure compared to what it would be if they had time to transition into an organized defense – though some coaches work to set up a suitable positional structure for the transition phases while attacking.

This is a video of the MNF where Carragher mentioned Chelsea’s positional structure in possession as a reason for their stability in the other phases of play – a good example to help everyone understand defending while in possession.

Attacking in this moment means the counterattacking team can take advantage of aspects that can be found when facing a disorganized defense – increased amounts of space, greater options, and less defensive pressure. When combined these aspects allow the attack to gain a valuable characteristic which is difficult to create and control against an organized defense – speed of attack. When facing a deep, compact, and organized press it is difficult for the players to ever reach “full speed” unless they properly prepare for the action and begin their movements ahead of time. It is the players with excellent acceleration and close control of the ball in tight areas that succeed in these situations.

Combining the previously mentioned aspects of a counter attack creates an atmosphere that is difficult to control for the defense. A full speed attack which has space, time, and multiple options is the perfect candidate to penetrate the defense and create high-probability goal-scoring chances. When defending at such high speeds it is much more difficult to maintain the body control necessary to quickly change directions, maintain balance, and read the situation in order to adjust properly.

This is made especially difficult as the defender has a reactive role in the engagement. He must defend the offensive player’s movements while the attacker is the one with the ball and thus can determine how the ball will move. At full speed, a talented attacker can add dribbles and feints to throw the defender off before penetrating the necessary space. But how much space is a defense truly covering when defending against Counterattacks?

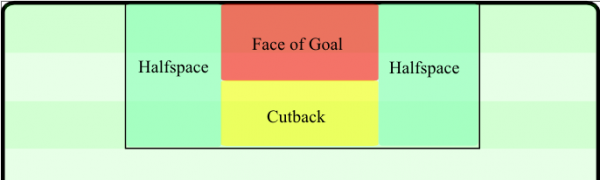

The width from half-space to half-space for most transitions is enough. The exposed defense cannot control all of the space efficiently and are open to combinations and quick switches from one half-space to another to penetrate.

Width – many people talk about this quality of attack as an extremely important aspect of any offense. So do counterattacks spread from touchline to touchline? No, they very rarely ever do. It’s very difficult to move the ball with pace and control from one touchline to the other consistently in modern football. What is important is relative width to the defense – an offensive team only needs to be wide enough to stretch the defense. Anything beyond that could have adverse effects depending on the team’s strategy. Do you want your winger to be on the touchline if the farthest the defender will move from the center of the field is to the edge of the box?

This is how most counterattacks work — they stretch from one half-space to the other at maximum! Most offensive transitions in football resemble the offensive transitions in basketball in this sense. In basketball there is a phrase which goes “filling the lanes in transition,” in football a similar action takes place as players fill the half-spaces and the center. So why does a “narrower” transition have better results than one which stretches from touchline to touchline?

This is because a player in each half-space is enough to stretch a defense which is low on numbers while maintaining a stronger (closer) connection between the attacking players. The distance from one edge of the box to the other is much shorter than it is from one touchline to the other – this means that passes are quicker, more accurate, and easier to control. If the offensive transition happens to stem from one of the flanks, then it is quite common to see the far-side winger completely abandon the flank and move into the center to maintain compactness.

These aspects together provide a favorable atmosphere for quick combinations in transition – which is particularly difficult for a defense because if they make a mistake they do not have the time needed to recover position in such a large amount of relative space. If the defense tries to pressure and fails (which is usually the case if there are smaller amount of defenders), then they must move across quite a large area to try and prevent penetration of the defensive line.

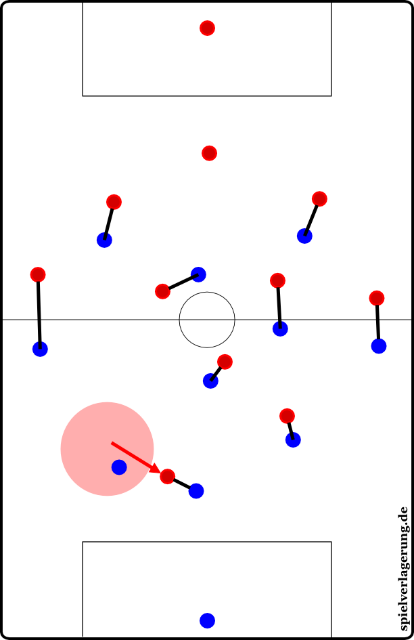

Given the multiple advantages of breaking through with a counterattack, it is important to differentiate the various strategies and tactical variations when it comes to offensive transition. Similar to counterpressing, the starting positions of a counterattack are determined by the positioning of the players while on defense. The defensive structure and strategy will relate directly into the strategy and structure for the offensive transitions. If the defensive team is compact on defense and win the ball, they are naturally in a better position to escape a counterpress through quick combinations with many players in the immediate area.

These zones can vary for specific strategies, but the majority of counterattacks can be broken down into the use of the center and half-spaces before penetration (or during creation) and in penetration (or during finishing). The flanks could also be included for various reasons even though they aren’t used as frequently.

When looking at counterattacks, these specific zones that I’ve outlined give an overview of the strategically different areas on the field. Teams usually try to break through the center and the half-spaces – the half-spaces are used more often due to the fact that the center is more concentrated with opponents in transition. Overloads in transition help to break through zones as well as use the value of the specific zone more intensely. For example, if the ball is won deep in the center of the pitch due to a pressing trap in a compact defense, the higher number of defenders become a higher number of attackers – which serves to overload the central zone and allow the players to combine out of the center and break into the flanks more easily.

Depending on the lineups and strategy of a specific team, the counterattacks will vary as well. A team like Real Madrid, who have Ronaldo and Bale out wide, press the flanks and remain compact so they can overload the flanks and break through the defense with their talented wingers – because it fits their players and their strategy. Where a team aims to win the ball on the field and which zones they aim to break into determine the nature of their offensive transitions – and these aspects are further determined by the coaching philosophy and strategy which stems from the types of players available.

Within the counterattacking strategies lie the tactics – such as how many players attack in transition and which passing, movement, and dribbling patterns are used. In regards to the thought process to escaping counterpressure and counterattacking, Pep Guardiola has mentioned that one of his principles is to first search for the long escape pass (preferably to the center forward or winger) and if it is not available to search for a safe short pass or combination to escape the pressured zone.

Besides playing vertical or diagonal passes in behind the defense into space for runners, there are combination strategies when it comes to the long pass into the forwards. The first low and long pass forward will search for the attackers – such as a “target man,” i.e. a player who is the focal point of the attack and can control the ball under pressure as well as create for others. A target man is commonly the center forward (classically, the #9), though a winger can be the target man as well. The positions which are naturally the quickest to move into high areas are the ones which begin in higher areas – such as the strikers and the wingers.

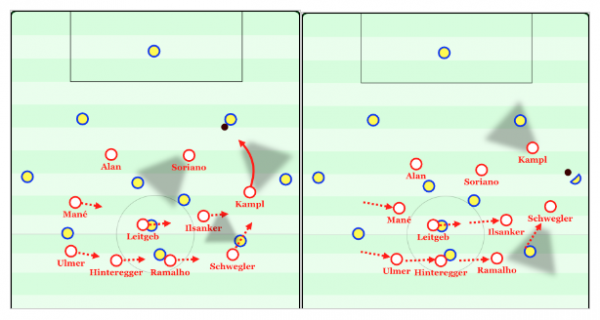

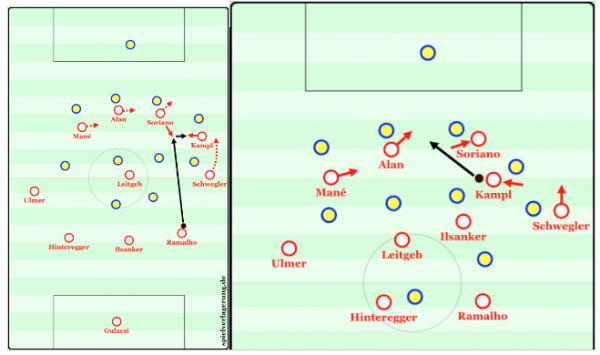

Though the situation isn’t exactly transitional – Salzburg’s goal here was to move Kampl into a creative position while have 3-4 runners ahead of him. A perfect example of an intermediary goal of a transition offense if the direct through pass isn’t available immediately.

The number of players which support the forwards varies depending on the strategy. With less players supporting the offensive transition, the atmosphere calls for more dribbling. With more players supporting the offensive transition, more complex combinations may occur to penetrate the defense. If the defense cannot be penetrated immediately with a through pass, an intermediate option in transition is to put one of the offensive players in a creative position – meaning a player who can receive the ball with time and space to play the penetrating pass to the forwards or even dribble and shoot.

Mourinho, and many other coaches, have talked about the principle of always having 5 players in defensive positions during an attack. So naturally his teams attack with 4-5 players while the other 6-5 push up behind the defensive transition to condense the space. I will use this common number as an example throughout my graphics, but it is important to know that counterattacks for any team could vary.

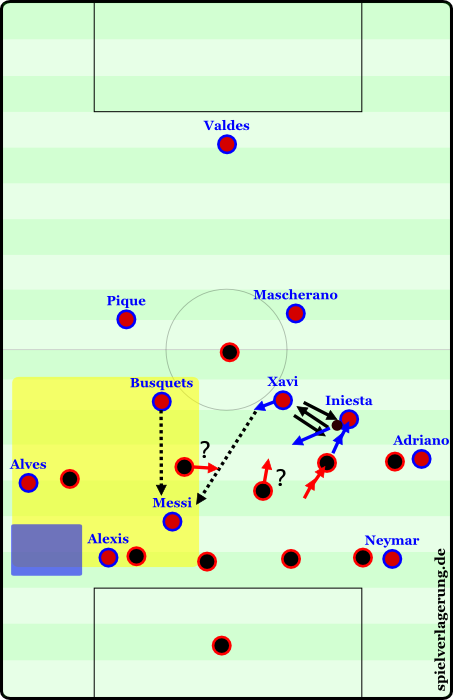

An example of Messi moving inside with his diagonal dribbling while the other runners make runs which bind the defenders, providing options for combinations, and opening space. This resulted in a Messi goal after he played the pass into the most central player and then received a lay-off. He also could have played the far side winger through unmarked.

The orientation of the counterattack can vary. In the case of Lionel Messi, he can receive the ball after a vertical pass into Suarez who lays it off towards Messi moving inside while the other players make penetrating runs for him. Or he could receive the ball directly to his feet and cut inside while the ball is on his left foot – therefore having his body between the ball and the defense. From there, he could dribble inside diagonally, play his long diagonal ball over the top, or move inside and combine with the forwards. The runs being made by the other attackers serve to both bind the defenders and to open space for Messi at the same time.

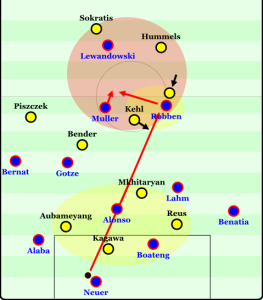

This image shows the effects of a lay-off pass after a long vertical pass. Pressure gathers around the destination of the ball (Robben) and opens space for Mueller to expose once he receives the lay-off as he is in stride and facing forward.

The previous example contained many important elements of counterattacks, such as – lay-off passes after a vertical ball, defender-binding runs by the attackers, and diagonality. A lay-off pass after a vertical ball attracts many players to the destination point of the ball before quickly moving the ball away to a teammate who is better positioned, has a good field of view, and can take advantage of the space created by the vertical pass into the forward as the defenders gather around him. The lay-off pass can be played with various techniques – the inside of the foot, the outside of the foot (which is more easily hidden and quicker), a back-heel pass (which would attract the attention of the defenders in the opposite direction of the pass – the direction of a players eyes plays a role as well), or a chipped ball over the feet of the defenders (a very underrated form of passing).

Two more passes are also interesting – the one-two and the “return pass.” A one-two pass or a “wall pass,” is a basic combination which uses an overload to move the initial ball player past his opponent quickly. Basically, in a 1 v 1 situation, another player can come create a 2v1 and the ball player can dribble towards the opponent and, once he has gotten close and forced the opponent to commit, then pass to his teammate before running around the opponent and receiving the return pass in space – this is a basic example of using an overload to break through a zone. This can involve third man, fourth man, and more runs off of the ball in more complex combination play.

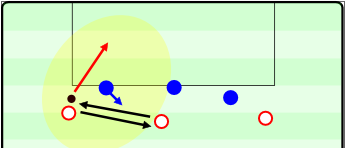

The effects of a return pass. The defender gets lured toward ball moving quickly between the players and leaves too much space open which allows penetration.

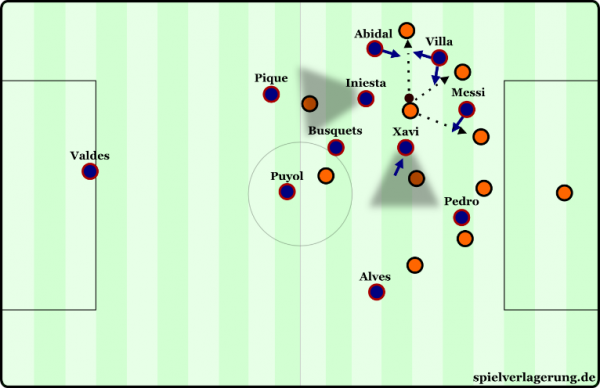

The “return pass” is used frequently in counterattacks as well as normal offensive organization. This is basically a 1-2 pass without the penetrating run. Iniesta, Xavi, Busquets, and Messi use this pass quite frequently between each other. The idea is simple – to lure the defender towards the ball before one of the players takes the ball and move into the space the defender vacated. In this example, the winger plays a pass to the center forward who immediately returns it to him, but the passing managed to pull the defender slightly more towards the center which allowed the winger to break through the space on the return pass. These types of passes can also include multiple off the ball runs as well.

In regards to specific types of passing, the principle of pass communication comes into play as well. Bielsa has said that there are 36 different ways to communicate through a pass – for example, a very hard pass into a players feet during a combination could be read by the player as the passer telling him to “dummy” the pass (let it go through him into a teammate further along the passing lane) or that the situation for the receiver will be very tight and difficult to solve so the speed of the pass had to be higher in order to enter the zone. That is only a few ways of communication through a pass, there are many more which could be explained in its own tactical theory article!

When looking at the “field of view” during combinations and offensive transition, there are many strategic values to this aspect of play. After the lay-off pass the receiving player can now have the ball while his field of view is forward and he can accurately assess the situation and make a decision. This would be much more difficult if the ball was played into the target man and he wasn’t allowed to turn – his field of view would only allow him to play backwards accurately.

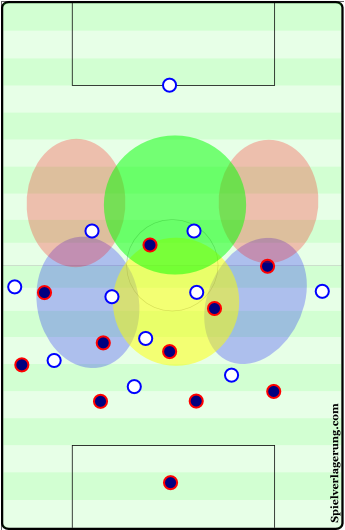

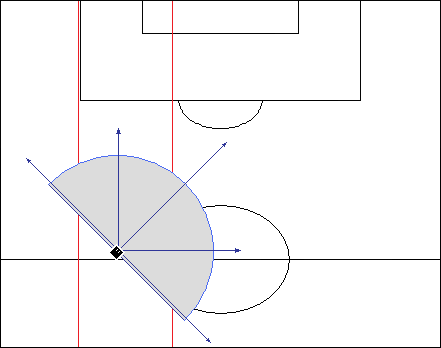

Field of view when facing goal from the half-spaces.

For a deeper analysis on half-spaces look here: The Half Spaces.

This also applies to the specific zones I’ve outlined earlier. The field of view when moving forward in the half-space means that the player is facing diagonally towards goal – allowing him to view options which are central and deeper than him, which wouldn’t be the same if the player was facing forwards – he would have to turn side to side to play passes towards the side. On top of that, the half-space is connected to both the center and the flank – so it has access to varied strategic zones, while the center can only move directly into a half-space on either side. The center is of course the most important area in football and many great synergetic effects arise from controlling this area.

Half-spaces have other nice characteristics in contrast to the center as strategic zones [include link to half-space piece]. If the field is divided into 5 vertical strips, the ball must move across 4 zones to go from touchline to touchline – which is very long and easy to defend. When inside the half-space, a player is connected to the near side flank directly and is 3 zones away from the far flank, which is easier to reach than 4 but is still a bit far – nevertheless it forces a defense to stretch and defend the far side a bit more.

The space-opening effects of the Barcelona players playing in one of the half-spaces.

If the player is in the center, he can play a pass across 2 zones (1 zone wouldn’t shift the defense very much) and reach the flank on either side, and the flank is strategically the least valuable zone as it’s so far from the opponent goal and the field of view is limited by the touchline. Though if the ball moved 2 zones from the half-spaces, it would move into the other half-space. So the ball can move a farther distance quickly and remain in a zone which is closer to the goal, which has multiple advantageous effects.

The importance of field of view applies to offensive transition as well in the fact that it can be a pressing trigger for a defense. When a player has first won the ball, his field of view is the worst as he has taken his eyes off the game to focus and take time to re-orient himself technically (controlling the ball) and tactically (seeing where his teammates are) – this is the moment most teams seek to press the ball (counterpressing). So it is important to have players in the immediate area to support the ball-winner and move the team into a more stable position.

Coaches in Barcelona have said that whoever has won the ball has done his job and doesn’t have to do anymore – he should look to pass the ball off to a teammate who has a better field of view to initiate the counterattack. There are always exceptions of course — if a player clearly intercepts the ball and has it under control quickly and didn’t take his eyes off the game for long, he can immediately initiate the offense transition.

Looking back at the Lionel Messi example, the idea of a forward’s runs binding defenders is important. When Lionel Messi cuts inside and starts dribbling diagonally toward the goal, Suarez or Neymar can look to make a diagonal run in the opposite direction of Messi right across the defenders. As he travels across the defensive line the defenders must pass him along to each other’s zones – this not only delays their movements towards the ball, but it also drags them in the direction of the run. This is because if the defender doesn’t follow the player, the player can just receive a pass in the space unmarked. So the defender follows the run to avoid the immediate threat, but he opens up the space he should be occupying.

So as Messi is dribbling inside he can either choose to play his teammates through the defense or use their space-opening decoy runs to drive into the created space and shoot. The space-opening runs can also open spaces for late-runners to move into untracked quite often – like Neymar running inside diagonally while Jordi Alba exposes the opened wide area. There are many advantages to these defender-binding runs – any movement from the offensive players has some sort of consequence. It can distort the defensive system, open space, offer a passing option, and more.

Evasive runs from the center or from the point of the ball are also a part of a striker’s movements. An evasive run refers to a run moving from the center into either side of the field towards the flanks. This can bind the defenders as well as create central space for wingers to move inside and combine or dribble through. Another aspect of this type of run is possibly creating a 1 v 1 situation on the flank once the striker’s run has ended. A similar run can be made away from the ball if needed – for example, if Cristiano has the ball on the left and Benzema is next to him and they are defended by two players, Benzema can move away from the situation in order to turn it into a 1 vs. 1 situation for Ronaldo by dragging his player away. This is advantageous due to the fact that a 1 vs. 1 situation in large amounts of space is less complex to deal with for a forward than a 2 vs. 2 situation.

This example takes the previous scene with Messi and highlights the effects of his diagonal dribbling instead. Messi will often move inside in this manner and “only” have to bypass 2-4 players at an angle with his body between the defender and ball. Because he is moving diagonally he evades a large portion of the team while moving towards goals and attacking an underloaded area. Respect Messi’s Diagonality!

The third aspect mentioned in the Messi example is diagonality. This simply means that a team has a high orientation towards diagonal play – similar to the term verticality. Diagonal play has multiple beneficial effects – one of which is the fact that it breaks both horizontal and vertical lines simultaneously. This causes defenders to make much more complicated movement than if the pass were only vertical or horizontal, meaning there is a larger room for mistakes in the chain-movements of the defense. A diagonal pass both directly gains space and shifts the field of play.

Facing the field diagonally from the flank or half-space means that the ball player is closer to the sideline while facing away from it – meaning he faces away from the least important space on the field at the moment and isn’t likely to receive backwards pressing. Taking into account the ball-oriented movement of every defense, they naturally “underload” the far side of the field and the farthest point of the ball because it is in the least amount of danger of being exposed – right? Well diagonal balls have these zones in their range (part of the reason Messi’s passes are so successful) as they can move long distances quickly while arriving in an area with minimal pressure.

Examples showing the value of diagonal passes even against deep defenses. Both of these situations resulted in goals after a Juanfran cutback cross in Atletico’s 3-1 victory of Chelsea.

Another interesting aspect regarding diagonal passes is the fact that in any given space, a diagonal pass from one “corner” to the other is the longest possible pass. So even if a defense has moved deep, they are still open to being exposed by a long diagonal pass behind them on the far side – whereas many defenses are used to dealing with shorter passes and obvious crosses when they’ve dropped deeper. Using diagonal passes and overloading the ball-far space which was under-loaded by the opponent defense is a common strategy against deep defenses. Real Madrid under Ancelotti, Atletico Madrid under Simeone, and Manchester United under Sir Alex Ferguson were some of the teams which did this frequently.

The final characteristic of diagonality I will mention is how it eliminates opponents on the route to goal. When Messi is moving inside diagonally he is “evading” a large group of players in the near side while moving towards the far side players and towards goal. While he is doing this the offensive players make runs which bind and drag more players into the space which Messi is dribbling away from – almost giving it the look as if he is going around a large portion of the defense and attacking the point at which the defense has a smaller amount of players to break through. This was particularly common in the seasons he played as a right winger under Guardiola and the current season under Lucho as he was allowed to gain more momentum when moving inside from the less crowded touchline (among other things).

The different strategic zones within the penalty box when looking to create a goal scoring chance.

*An interesting piece by Michael Caley on the value of making extra passes in the “Danger Zone” can be found here.

When finishing off counterattacks, the main goal of the team is to penetrate the penalty box – be it through passing or dribbling. I’ve outlined the most important zones in the box in the image above – with most of the penetrations coming in the half-space areas. After penetrating the box, most of the best goalscoring chances come from a very fast and low pass across the face of goal for a tap-in (depending on the positioning of the defenders) or a fast and low cutback pass moving away from the goal and taking advantage of the defenders’ backward-moving momentum. The passes across goal end up in the higher central zone while the cutbacks end up in the deeper central zone. Shots directly from the half-space after penetration is another efficient (but less efficient than making the extra pass?*) form of scoring.

Other good approaches involve diagonal dribbles towards the box and combining to break through or continuing the dribble and shooting – though these may be more difficult than the previous options. As mentioned earlier, long diagonal balls towards the weak side of the defense (be it for headers or to play into feet) are also an efficient form of finishing off an attack – though it can involve lower percentage aspects depending on the specific situation.

Finally, there are some interesting psychological effects when it comes to counterattacks. The quick impulse to switch the player’s mindset from defense to attack is highly important when it comes to offensive transition as it could mean exposing the opponent with greater speed. The fact that there are larger amounts of space to play into during a counterattack also has an important psychological effect on the players. As they are moving at high speed and into large amounts of space, they make decisions which are much more aggressive, direct, and confident – as opposed to the more cautious and thinking approach if the spaces were to have more defenders.

Mourinho’s Inter in 2010 were interesting in part due to their wider horizontal defense instead of defending in a narrow and horizontally compact fashion in some scenes. As you recall from the earlier parts of this piece, Inter didn’t want the ball – so they just moved towards the ball passively and sought to prevent penetration. Barcelona could switch the ball through midfield very easily because of that. The interesting part came when switching the ball, because whenever the ball would move to the “weak side,” Inter would already have players there as they weren’t so horizontally compact – and the players never sought to win the ball so they weren’t easily pulled out of the shape.

This forced Barcelona’s overloads on the weak side (Maxwell and Pedro for example) to have an inefficient positional structure to break through the Inter defense in the overloaded zone. Maxwell stayed a bit deeper as he wanted to be sure to receive the ball and there was less opportunity to move vertically because of that. Combination play in football is all about minor positional advantages, be it on the ball-side or goal-side. It’s similar to basketball in this sense as well because in basketball multiple “picks” or “screens” are set in order to give one team a positional advantage over the other.

In the end, the players had to think with the ball more and delayed their actions (decisions and executions) – the best moments of penetration came when Xavi or Messi were involved because they are excellent decision makers as well as having the necessary technical execution.

ANYTHING ELSE

To finish off I’d like to elaborate on the philosophy of Lillo and Guardiola as well as some other coaches. The idea is that phases of the game do not exist. They do not separate the game into “offensive organization, defensive organization, offensive transition, and defensive transition,” but they view the game as a continuous flow of specific positional structures which the team is trying to achieve.

Of course one team will still have the ball and another team won’t, but this is not as important as the positioning of the players themselves. As I mentioned throughout the piece – it is possible to attack while defending and to defend while attacking. This is why separating the game into the traditional 4 phases misses some of the complexity that’s involved in the game. Some players might be in a specific phase of play while their teammates are doing something differently – so it is difficult to categorize the entire team into a collective game phase.

The way they view the game is through the positioning of players in relation to the reference points of the game to form a collective positional structure. Regardless of what’s happening the team should seek to have a good structure and ball-oriented shape – this will provide the stability and efficiency needed in every situation.

To use the traditional game phases in order to better explain this: when in possession, the team want to have a positional structure which is efficient for attacking but would help them counterpress the ball or drop deep if they lose it. While transitioning to defense the team seeks to have a positional structure which is best for pressuring the ball or protecting the goal, but also translates well into the other phases.

The general idea is that on the hierarchy of importance, the positional structure of the team is more important than who has the ball or which “phase” the game is in. The team only seeks to have a specific positioning in relation to what is happening in the moment and play that way throughout the game. These guidelines to the specific positioning and movements during the game are all coached to the players and worked on throughout the season. The game is different when viewed through the idea that a team is only ever seeking the appropriate positional structure to what is happening throughout the match rather than viewing it through the recurring traditional four phase cycle which could lose some of the complexity of the game.

* Adin Osmanbasic is a football coach and analyst.

BUSCADOR DE CATEGORÍAS

BUSCADOR POR MES

ÚLTIMOS TWEETS

Tweets por @martiperarnauSÍGUENOS EN FACEBOOK